Marfan syndrome

Background

- Marfan syndrome (MFS) is a heritable connective tissue disorder with multi-system involvement[1]

- First characterized as a syndrome by French pediatrician Antoine Marfan in 1896

- Clinical features vary along a spectrum typical of autosomal-dominant disorders

- Autosomal-dominant mutation in FBN1 gene (encodes collagen matrix protein fibrillin-1) on chromosome 15[1]

- This results in cystic medial degeneration of the aortic tunica media (leading to increased risk of aortic aneurysm / dissection)

- This also interferes with elastin deposition during extracellular matrix formation implicates in the elasticity of multiple tissue types

- Majority of cases (75%) are familial / inherited vs. minority (25%) are de novo mutations

- Estimated prevalence of 1/5000 individuals worldwide (equal between men and women)[1]

- Life expectancy for those diagnosed and treated is now close to that of non-MFS population (previously expected increase in patient mortality by third and fourth decades of life)

Clinical Features

Physical Findings

Not all may be present

- Tall stature, long extremities

- Reduce upper-to-lower segment ratio, increased arm span-to-height ratio

- Arachnodactyly (“wrist sign, thumb sign), reduced elbow extension

- Scoliosis or thoracolumbar kyphosis

- Pectus excavatum or carinatum

- Ligamentous laxity, hyperextensibility

- Protrusio acetabuli

- Hindfoot deformity, plain flat foot

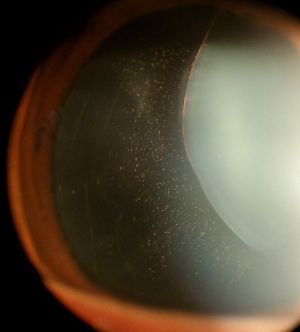

- Ectopia lentis

- Myopia (often severe); retinal detachment

- Lumbrosacral dural ectasia

- Dolichocephaly, downward slanting palpebral fissures, enophthalmos, retrognathia, malar hypoplasia, high arched palate

- Skin striae

Increased Risk[2]

- Acute Aortic Syndrome (AAS)

- Thoracic aortic aneurysm

- Stanford Types A and B aortic dissection

- Intramural Hemotoma (IMH)

- Mitral valve prolapse (present in up to 60%) and mitral regurgitation

- Spontaneous pneumothorax (associated with bullae, 4-11%)

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage[3]

- Controversial link between Marfan Syndrome and intracranial aneurysms (more clearly associated with vEDS and LDS)

- Ocular Lens dislocation, retinal detachment

- Spinal conditions (scoliosis; lumbosacral disease; dural ectasia)

- Musculoskeletal injuries due to joint laxity (laxity in 85% of children, 56% of adults)

- Complications during pregnancy (risk of aortic dissection)

- Type A dissection risk increases with aortic dilation; Type B risk poorly understood. (aortic dissection in up to 4.5%, primarily peripartum)

Differential Diagnosis

- Classic vs. Kyphoscoliotic vs. Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (vEDS)[4]

- Loeys-Dietz Syndrome (LDS)

- Familial Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection (FTAAD)

- Familial Ectopia Lentis Syndrome

- MASS Phenotype (Myopia, Mitral Valve Prolapse, Aortic Root Dilatation, Aortic Aneurysm Syndrome, Striae, Skeletal Findings)

- Shprintzen-Goldberg Syndrome

- Beals Syndrome

- Stickler Syndrome

- Non-Specific Connective Tissue Disorder

Evaluation

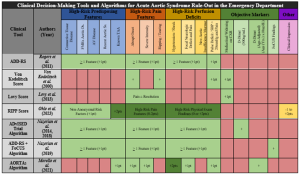

TOP: Flowchart of ADvISED Trial Algorithm. BOTTOM: flowchart of AORTAs Algorithm[5].

Summary of currently published clinical tools for acute aortic syndrome in the ED, with respective components and scoring systems.[6]

Workup

- Initial evaluation often occurs in the outpatient setting and involves a thorough physical exam for identification of classically associated features, review of family medical history, slit lamp dilated pupil eye exam (to evaluate for ectopia lentis), and echocardiogram.

- Advancement to specialist involvement, review of transthoracic echocardiography for aortic root dilation / aneurysm / heart valve involvement, potential genetic testing and/or medical genetics consultation per current guidelines.[7]

Acute Aortic Syndrome (AAS)

- A high index of suspicion for AAS in the ED setting is critical in MFS when symptoms or signs of this life-threatening complication occur.

- Key Elements:

- Sudden onset of severe, “thunderclap” quality, potentially “tearing” and/or migratory chest, neck, abdominal, and/or back pain

- Young patients with few traditional cardiovascular risk factors

- Current or recent pregnancy

- Family history of aortic aneurysm/dissection or unexplained sudden death

- Typical “Marfanoid” features may not always be present, especially in non-white patients

- Clinical decision-making tools and algorithms are available (e.g., ADvISED Trial ADD-RS + D-dimer, AORTAs Algorithms), but are not yet externally validated (see images).[8]

- Basic labs, troponin, D-dimer

- Important Note: D-dimer is not 100% sensitive and cannot exclude all acute aortic syndromes

- EKG, CXR

- CTA / MRA aortic protocol (with IV contrast)

- Bedside POCUS (Left ventricular outflow tract, aortic root, aortic valve, pericardium, abdominal aorta survey)

- Formal TTE / TEE

Other Emergencies

- Standard workup as with non-MFS patients

Diagnosis

Revised Ghent Nosology (2010)[4]

In the absence of family history:

- Aortic Root Dilatation Z Score > 2 and Ectopia Lentis

- Aortic Root Dilatation Z Score > 2 and FBN1 Mutation

- Aortic Root Dilatation Z Score > 2 and Systemic Score > 7 points

- Ectopia Lentis and FBN1 Mutation (associated with aortic root dilatation)

In the presence of family history:

- Ectopia Lentis and Family History of MFS

- Systemic Score > 7 points and Family History of MFS

- Aortic Root Dilatation Z Score > 2 (above 20 years old), > 3 (below 20 years old) and Family History of MFS

Aortic Dissection Classification

- Stanford

- Type A: Involves any portion of ascending aorta

- Type B: Isolated to descending aorta

- De Bakey

- Type I: Involves the ascending and descending aorta

- Type II: Involves only the ascending aorta

- Type III: Involves only the descending aorta

| Image |

|

|

|

| Percentage | 60% | 10–15% | 25–30% |

| Type | DeBakey I | DeBakey II | DeBakey III |

| Classification | Stanford A (Proximal) | Stanford B (Distal) | |

Management

Medications

- Beta-Blocker and/or Angiotensin II Type 1 Receptor Blocker (ARB) Therapy

- Beta-blockade lowers blood pressure / heart rate and reduces aortic wall shearing forces to reduce the rate of aortic aneurysm growth and risk of dissection

- Inhibition of ATII Type 1 Receptor-mediated TGF-beta signaling may reduce elastic tissue degeneration based upon mouse models.[9]

- Other Pharmacologic Considerations

- Avoid fluoroquinolones (FQs) due to matrix metalloproteinase activation and increased risk of aortic aneurysm/dissection

- Chen S-W et al. (2023) did not show a significant increase in aortic aneurysm/dissection (OR 1.000) in MFS and other high-risk patients after FQ administration.[10]

- Gopalakrishnan et al. (2020) showed a significant increase in aortic aneurysm/dissection in patients receiving FQs for pneumonia (HR 2.57, p<0.01%), but not UTIs (HR 0.99, p<0.01%). This suggests intrathoracic inflammation from the primary disease pathology, not FQs themselves, increase the risk of aneurysm or dissection.[11]

- Antibiotic prophylaxis is no longer recommended for MFS patients before dental procedures, except in those with artificial heart valves

- Avoid fluoroquinolones (FQs) due to matrix metalloproteinase activation and increased risk of aortic aneurysm/dissection

Lifestyle Modifications [12]

- Regular blood pressure measurement, lifestyle modification, and titration of antihypertensive therapies with goal BP < 120/80 mmHg

- Avoidance of high-intensity, high-impact sports and intensive isometric activities / weightlifting

- Low- to moderate-intensity aerobic activities are encouraged after discussion with a cardiologist or specialist

- Avoidance of Valsalva and other maneuvers that increase intrathoracic or abdominal pressure (risk of acute dissection)

- Avoidance/cessation of tobacco, smoking, vaping, or stimulant abuse (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamines)

- Psychiatric evaluation, resources, and support groups (e.g., Marfan Foundation, oeys-Dietz Syndrome Foundation) as appropriate to help address psychosocial sequelae (e.g., body dysmorphia, anxiety, depression, PTSD, suicidal ideation)

Emergency Management [13] [14]

- Evidence-based management of acute aortic dissection:

- IV medications to reduce blood pressure (< 100–120 mmHg) and heart rate (< 60 bpm) (e.g., esmolol, labetalol, nitroprusside)

- Emergent vascular, cardiothoracic, or other surgical consultations

- Definitive management per current guidelines based on Stanford Type A vs. B dissection, location, extent, and branch involvement

- Standard-of-care treatment for other associated pathologies

Disposition

- Disposition depends upon the chief complaint, clinical gestalt, and objective findings from physical exam and workup.

See Also

External Links

- Marfan Foundation

- Marfan Foundation (Resources for Physicians)

- Genetic Aortic Network - formerly GenTAC Alliance

- International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Milewicz DM, Braverman AC, De Backer J, et al. Marfan syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):64. doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00298-7.

- ↑ Dean, J. Marfan syndrome: clinical diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:724-733. doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201851

- ↑ 4. Kim JH, Woo Kim J, Song S-W, et al. Intracranial aneurysms are associated with Marfan Syndrome: Single cohort retrospective study in 118 patients using brain imaging. Stroke. 2020;52(1):331-334. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032107

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 The Marfan Foundation. (2025, May 21). The Marfan Foundation | Know the Signs | Fight for Victory. Marfan Foundation. https://marfan.org/

- ↑ Pena RCF, Hofmann Bowman MA, Ahmad M, et al. An assessment of the current medical management of thoracic aortic disease: A patient-centered scoping literature review. Seminars in Vasc Surg. 2022;25(1):16-34. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2022.02.007

- ↑ Pena RCF, Hofmann Bowman MA, Ahmad M, et al. An assessment of the current medical management of thoracic aortic disease: A patient-centered scoping literature review. Seminars in Vasc Surg. 2022;25(1):16-34. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2022.02.007

- ↑ Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Black JH, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: A report of the American Heart Association / American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;146(24):e334-482. doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001106

- ↑ Pena RCF, Hofmann Bowman MA, Ohle R, et al. Algorithms and clinical-decision-making tools for ruling out acute aortic syndrome in the Emergency Department: A narrative review. Italian Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2024;31(1):42-53. doi:10.23736/S1824-4777.23.01623-6

- ↑ Pena RCF, Hofmann Bowman MA, Ahmad M, et al. An assessment of the current medical management of thoracic aortic disease: A patient-centered scoping literature review. Seminars in Vasc Surg. 2022;25(1):16-34. doi:10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2022.02.007

- ↑ Chen S-W, Lin C-P, Chan Y-H, et al. Fluoroquinolones and risk of aortic aneurysm or dissection in patients with congenital aortic disease and Marfan Syndrome. Circ J. 2023;87(9):1164-1172. doi:10.1253/circj.cj-22-0682

- ↑ Gopalakrishnan C, Bykov K, Fischer MA, et al. Association of fluoroquinolones with the risk of aortic aneurysm or aortic dissection. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(12):1596-1605. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.4199

- ↑ The Marfan Foundation. (2017). Physical Activity Guidelines. https://marfan.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/FINAL-Physical-Activity-Guidelines-11_17.pdf

- ↑ Reed MJ. Diagnosis and management of acute aortic dissection in the emergency department. Brit J of Hosp Med. 2024;85(4). doi:10.12968/hmed.2023.0366

- ↑ Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Black JH, et al. 2002 ACC/AHA Guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: a report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. JACC. 2022;80(24):e223-e393. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.08.004